By Sylvie Kirsch

Medill Reports

LONDON — In London for only 36 hours, I had one must-stop on my itinerary: the winding black and green aisles of six-story 187 Piccadilly, home of Hatchards, the oldest bookstore in the city. Built on tradition and cache, Hatchards, a favorite of Oscar Wilde and King Charles, continues to sell physical books in a digital-dominated landscape and can print any British title on demand.

At the helm: Francis Cleverdon, an Oxford graduate and ex-artisan printer of pad-typed poetry volumes who has managed the shop and its 40 expert booksellers since 2014. In a trim, green tweed suit and thick-rimmed glasses, he sat down to discuss how Hatchards’ business model has changed over the past 227 years (spoiler: not much), how he helps it keep its elite bookselling status, and how you can land a job there this holiday season.

***

Was this your dream job?

Yes. Once a term through primary school, we were allowed to come to tea at Fortnum & Mason next door and buy one book at Hatchards. So, I always wanted to be the Hatchards manager. It is the best job in London, bookselling.

What is Hatchards’ history?

Hatchards started life as an anti-slavery bookshop. Aristocratic Tories would gather to campaign here until slavery was abolished in 1833. One of the first books ever written by an ex-slave, Olaudah Equiano, was first published by Hatchards. We then expanded into more of a literary bookshop in the later 19th century. We had very close ties to Oscar Wilde and that Tite Street lot (where Wilde and famous artists such as James McNeill Whistler lived).

So, do writers ever visit Hatchards for inspiration?

A great American academic came who had been researching Jane Austen. He found a letter from Jane to her sister, Cassandra. Jane had been into Hatchards, bought a copy of “The Castle of Otranto” and wrote, “I think we can do something with this.” And that was the start of “Northanger Abbey.”

What’s the hiring process like, including for seasonal positions? Do you have to take a test?

It’s not a tough interview, but there are questions like, “Have you read enough? Can you wax lyrical about the last book you read?” And you don’t look blankly at us when we say, “Which do you think is the best Austen novel?” There’s no right answer. It’s just whether you’ve actually read them.

It has to be said: We pay extraordinarily badly. It puts off quite a lot of people. But we do get a lot of people asking, and I suppose it’s because we’re a rather romantic shop.

Have any of your booksellers fallen in love with each other?

Oh, absolutely! About once every three years we have a shop marriage. God, the affairs. I usually find out late. The first I know about it is the girl is weeping in the corner because they’ve broken up.

General manager Francis Cleverdon sits at his desk at Hatchards’ flagship Piccadilly bookstore. (Sylvie Kirsch/MEDILL)

You’ve been open since 1797. How has your business model evolved?

It’s changed with the times. We started out as much of a publisher as we were a bookseller. And apart from our limited edition of out-of-print title service, we don’t publish any new books today.

Another part of the 19th century was Hatchards’ bindery. People would come, and we’d bind in their binding anything they bought. So, the Duke of Devonshire always had dark blue bindings, and the Duke of Rutland always had dark red bindings, and we would bind everything to them to match. That’s gone. We will get things bound for people if they want, but it’s not a core part of us.

What is your connection to the royal family?

We started out early with the royals because they were attached to the Tory crowd. The first record of us selling to them was a book to Queen Caroline in 1810.

You have three Royal Warrants, designating you an official seller to the royal family. What does that mean?

For foreigners, it’s a bizarre piece of Englishness and makes Hatchards feel very old-Englishy. In the real world, it means we’re meant to be good and guarantees we really try. To any question, the answer should be “Yes.”

What was the last royal visit you had?

I’m not allowed to tell you. I’m terribly sorry. It’s too dangerous. The classic Royal Warrant story is that there’s a wonderful bra shop that got rung by somebody and managed to tell them the queen’s bra size. They lost their Royal Warrant so fast you would not believe it. I mean, how could they?! That is the ultimate question that you must not tell. So, we’re not allowed to tell you what they buy.

Should they ring us up and say, “I don’t know what to get everybody, oh God,” then we’re quite willing to open the shop late. And they wander about.

Were you here for that?

I might have been.

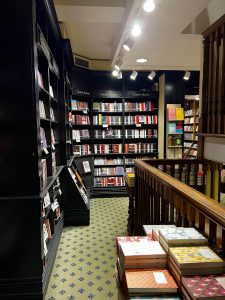

The winding corridor of Hatchards’ third floor, where much of its classical literature selection is housed. (Sylvie Kirsch/MEDILL)

Walk me through your monthly subscription package.

We find out what you like and what you fling at the wall in fury. Then we go into the shelves, find a book that fits, wrap it up in brown paper and ribbon, and put it in the post.

One very sweet, romantic subscription is for a scientist in the Antarctic, and every month we send off the book and picture it hissing across the ice behind a husky.

Tell me about your rare and secondhand book service.

We brought the service back in 2019, decades after it disappeared. You have to have a rather rich clientele, but it works. We’ve got an original copy of “Mrs. Dalloway” (byVirginia Woolf). We had to have it because Mrs. Dalloway walks down Piccadilly and looks in Hatchards’ front window.

We’re looking for offers. It’s only 25,000 pounds ($31,657).

How does this rare book collection contribute to Hatchards’ cache?

We’re unashamedly expensive. We never discount anything. Our footfall is probably the richest in the world, with the billionaires living in the Ritz and all that sort. And our rare books emphasize that idea.

The ground floor of Hatchards. (Sylvie Kirsch/MEDILL)

The ground floor of Hatchards. (Sylvie Kirsch/MEDILL)

Viral “BookTok” titles are dominating U.S. bookstores. Has BookTok changed Hatchards’ revenue stream or titles carried?

It’s silly to say, “No, it hasn’t.” There’s a table in fiction on the first floor — basically those. I keep battling to say, “Do we really need these?” And my booksellers tell me, “Yes, Francis, we do. You’re just too old!” But the wonderful thing is, they work. People read. There were more books sold and read last year than ever before.

In America, there’s a large conversation going on surrounding book banning. Do you ever foresee Hatchards censoring a title on its shelves?

I’m of the generation that I would never say, “We should not do this book.” There was a big, big row in the 1990s about whether we should stock a particularly nasty historian called David Irving. And I was on the side of, “It’s not up to us to make a decision about whether things are right or wrong. It’s up to us to provide the wherewithal for people to make their minds up.” And while I’m manager, that will be the attitude. But my staff are quite right to come and beat me in the head, saying, “You must be mad” and “This is immoral.”

Do you see famous patrons regularly here?

Quite a lot. You’ll tip-tap down the stairs and think, “Good Lord! Wasn’t it empty just now?” Because all of a sudden there are 22 people on the ground floor. And you realize that they’re not actually moving, nor are they looking at the books. They’re just at strategic points. And you know that somebody’s in the shop. Then, bringing up the rear is a poor, shambling Cockney detective who’s trying to make sure that this blaney lot of foreign bodyguards don’t bloody shoot somebody. It’s quite funny.

Why is Hatchards so special?

I’m sure my equivalent 200 years ago would have said the same: It’s important we’ve got the books and staff who know the books and that we do anything we possibly can — short of actively paying people to buy from us.

Sylvie Kirsch is a recent graduate of Medill’s magazine specialization. You can find her on LinkedIn.