By Sara Cooper

Medill Reports

Dan Caselden had little interest in astronomy before he became an expert in identifying undiscovered celestial bodies. Scrolling through social media in 2017, he heard of a digital project called Backyard Worlds: Planet 9 where he could volunteer his time to help astronomers identify rogue planets, brown dwarfs and potentially even a hypothesized ninth planet at the fringes of our solar system. He was hooked.

“The way they presented it was as a needle-in-the-haystack, data-style problem,” said Caselden, who works professionally as a software engineer. “That on its own is a good draw.”

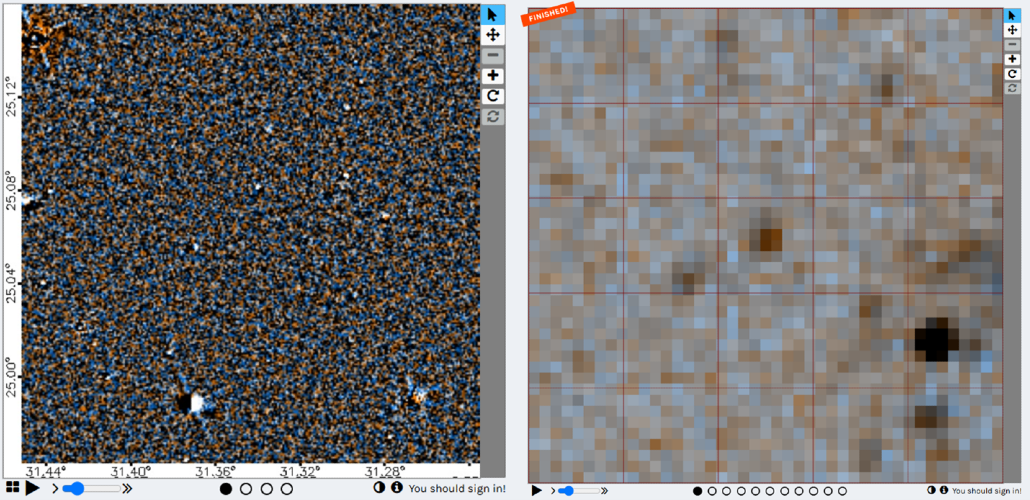

Caselden joined more than 85,000 global volunteers on the Planet 9 project, flipping through millions of images from NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) telescope to find moving objects that might represent undiscovered planets or larger substellar objects known as brown dwarfs. As Caselden became more involved in collaboration with researchers and fellow volunteers, he had a thought: This could be a job for AI.

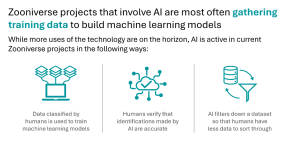

Planet 9 is a classic example of citizen science, a practice that tackles issues of large-scale data collection, processing and analysis by crowdsourcing volunteer effort. Hosted on the Zooniverse, one of the mostcitizen science platforms with nearly 3 million registered volunteers, Planet 9 is among dozens of projects on the site that have inspired AI integration. Contrary to fears of automation replacing the human element, however, these projects demonstrate how AI has the potential to strengthen those qualities that inspire citizen scientists to volunteer their most valuable resource of time.

In 2023, six years after the start of Planet 9, an AI-enhanced twin called Backyard Worlds: Cool Neighbors launched on the Zooniverse. Tasking volunteers with a similar type of object detection, Cool Neighbors had one major difference to Planet 9 — it used a machine-learning algorithm developed by Caselden to pre-select areas of the sky most likely to contain objects of interest.

The result was nearly three times the number of classifications in six months compared with Planet 9.

“To us there’s a narrative where the idea of focusing on smaller, targeted areas led to better engagement and better performance,” said Aaron Meisner, principal investigator behind the Backyard Worlds projects. “There’s a synergy with connecting machine learning in a way that made the volunteer’s time better spent and retained their efforts longer.”

For a platform that relies on the passion of volunteers, many of whom are inspired by the possibility of making novel scientific discoveries, the ability to increase their success rate can be key to strengthening engagement on the Zooniverse.

“It’s a really good hybrid model,” said Cliff Johnson, Zooniverse director and science lead. “We’re able to combine the best parts of machine learning by getting rid of all the boring rote things that the machines are really good at and focus the human attention on the parts that are still unknown.”

The need for this human input isn’t going to be replaced by AI any time soon. As Cool Neighbors shows, even when trained on millions of images, the capabilities of machine learning models are limited.

One reason is data in fields like astronomy often require low-signal noise detection. Objects of interest typically don’t stand out clearly from background information, and machines can struggle to make reliable identifications.

More fundamentally, algorithms can be at odds with the nature of scientific discovery.

“Even if you could make the AI orders of magnitude better, there’s still the human element in discovering things that you didn’t even realize you were looking for,” Meisner said. “There’s a serendipity that comes from the fact that each participant has their own pet interest.”

Still, there remains ample room to expand the use of AI in citizen science. One potential area is in implementing individualized AI feedback to help volunteers level-up their abilities, enriching their learning experience in the process.

Lucy Fortson, an astronomer at the University of Minnesota and co-founder of the Zooniverse, envisions a cooperative model where human data can train machine-learning models while that algorithm, in turn, can provide feedback to help volunteers sharpen their ability to identify and classify relevant data.

“If volunteers are thrown into the deep end on a difficult task, some of them may just leave,” Fortson said. “You can have a human novice learn and a machine novice learn at the same time. The machine becomes a coach, but the coach can be corrected by the humans as well.”

While enthusiasm over AI is relatively high among both researchers and citizen scientist volunteers, common ethical concerns around data privacy and mistrust remain. Yet just as AI can highlight the appealing features of citizen science, pushback against its use also echoes those pre-existing concerns.

“Some papers are fiercely critical of participatory science in the form of citizen science,” said Marisa Ponti, a professor of informatics who studies human-centered AI at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden. “This concern with the possibility of exploiting people existed far before the use of AI. AI doesn’t introduce a new element, it can just amplify or exacerbate something that already exists.”

For scientists using the Zooniverse, these ethical concerns demand careful consideration of how they present AI features in their projects.

“We have to do this very intentionally and very methodically,” Fortson said. “The trust that we have with our volunteers, we absolutely do not want to break. We have the opportunity as a platform to be one of the few places where AI can be transparent, and we don’t want to lose that.”

As Fortson suggests, the field of citizen science may present a unique space for regular people to engage with and learn about AI. As we head towards a future where automation is increasingly difficult to opt out of, education on the utility, limitations and basic operation of AI may alleviate anxieties around the technology for the Zooniverse’s nearly 3 million users.

“It’s a good case that someone who is participating in this can basically see the entire life cycle (of machine learning), from their inputs to the final outputs of what it’s used for,” Johnson said. “It addresses a lot of the questions and concerns that people have about AI in general. Anything we can do as a platform to help educate our volunteers and dispel people’s fears about the unknown, that’s a huge win for us.”

To learn more about AI and its potential applications in the Zooniverse, explore this collection of papers, The Future of Artificial Intelligence and Citizen Science, from the journal Citizen Science: Theory and Practice.

Sara Cooper is a Health, Environment and Science graduate from Medill. You can see more of her work on her personal website.