By Alyssa Rola

Medill Reports

Every time she gets sick, Wanmin Zhang habitually looks for her personal cure: her parents’ home-cooked Chinese meals.

The 28-year-old support engineer, who was born in southern China but grew up in Chicago, can only fend for herself as an adult. She’d visit Asian grocery stores to cop intricate ingredients and spices that aren’t normally found in American supermarkets.

“Whenever I walk into an Asian grocery store, I just remember my parents taking me there,” Zhang said. “We go on these shopping trips, and they always buy me these snacks, jelly candies that I really like, and chips. It just brings me that warm, fuzzy feeling.”

For immigrant communities, supermarkets represent more than a shopping spot. They double as a place where people can reconnect with their first homes and fellow countrymen. But economic challenges like inflation and tariffs threaten the local industry, leaving businesses and customers with no choice but to pay and pray.

Recent data from the National Grocers Association showed that in 2024, 94% of consumers expressed concern over inflation and tariffs, which formally took effect Aug. 7.

Zhang herself had noticed steady price increases over the years. She’s now paying around $6 for a pack of egg tofu, which she used to grab for just $2.

But while mainstream grocery stores like Jewel-Osco and Aldi remain options, Zhang said she’ll still come back to Asian supermarkets.

“For Chinese people, they have that sense of familiarity, where they can breathe and interact with people,” Zhang said.

Grocers as second home, ‘cultural bridge’

Several international supermarkets meet the needs of immigrant communities who settled in the city. More than 700,000 Asians – the majority from India, the Philippines and China – are in the Chicago metro area, according to the U.S. Census.

Over the past decades, both corporate and family-owned cultural grocers have spread across the city’s neighborhoods. Patel Brothers, the largest Indian grocery chain in the country, started in Chicago because its owners missed their native food, a sentiment echoed by other members of their community.

Zhang shared how her parents found a safe space in these shops, where they can talk to anyone in their own language.

“They don’t speak English very well, but there (Asian supermarkets), they can buy whatever they need to buy, understand what everything means and see the familiar items that they’re used to eating and cooking with,” she said.

International supermarkets serve their customers in multiple ways, including cooking mom-style meals to go, a plus for those without time to work in the kitchen.

Leticia Alerta, owner of Ian Mae Oriental Store in suburban Niles, said some loyal customers come in every day to get best-sellers like turon (banana spring rolls) and pansit noodles.

The shop, which originally opened as a meat market in 1985, offers other popular Filipino home-cooked meals like lechon kawali (deep fried pork belly), laing (taro leaves in coconut milk) and menudo.

“It really helps a lot, especially for people working double jobs who have no time to cook,” Alerta said. “(Immigrants) here work 16 hours (a day). They don’t have time to cook. That’s what we do for them.”

Some supermarkets also try to introduce Asian culture to different audiences.

In River West, Gangnam Market – named after a popular South Korean district – is quickly gaining popularity on social media for its bright neon lights and trendy snacks like the viral mango ice cream bars and crab rangoon pizza.

The store hosts different activities, including mahjong games, K-pop dance performances and anime exhibitions, for all ages and backgrounds.

Content creator Gabriela Cubero said these supermarkets, with the help of social media, can be a great platform to showcase something new.

“When I go to H Mart, I’m always intrigued by different fruits,” Cubero said. “So I’ve learned so much about lychees, rambutan — things that I sometimes don’t see on the regular.”

Higher prices seen in supermarkets

Economists see a challenge for supermarkets – especially those sourcing from other countries – following the rollout of the U.S. government’s tariff rules. For one, they said the higher levy applications will trigger a further hike in supermarket prices once current stocks are depleted.

Ian Coxhead, senior research fellow at the Institute of Developing Economies in Japan and professor emeritus at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, said food commodities “operate on very narrow margins,” giving “little scope” for producers and exporters to fully absorb tariffs.

“I expect that once existing stocks are exhausted, we will see more or less 100% tariff pass-through to supermarket shelf prices,” Coxhead said.

Since taking office, President Donald Trump has imposed new tariffs for more than 90 countries to protect America’s trade and manufacturing industry as well as to promote domestic economic growth.

A “universal” 10% tariff baseline took effect in April, but some countries – especially those with which the U.S. has trade deficits – face higher rates. Major trading partner China was slapped with more levies, including on chemicals used to make fentanyl, as Washington and Beijing struck a new deal in November. Vietnam and the Philippines, on the other hand, get 20% and 19%, respectively.

But when can consumers formally feel the effects?

Melissa Lopez, chief economist for the Association of Southeast Asian Nations at Lundgreen’s Capital, said a significant number of Asian producers employed an export “front-loading” strategy, or accelerating shipments to America before tariffs increased.

“I don’t see a shortage anytime soon,” Lopez said. “There are still stocks for the short term, maybe a few months’ worth of inventory.”

Cutting “discretionary” items and switching to lower-priced options can ease the tariffs’ impact on consumers, she said.

Smaller businesses to take hardest hit

Smaller Asian stores, including mom-and-pop shops, will likely bear the brunt of the U.S. government’s sweeping new tariffs, economists predict. Business owners, for their part, are doing their best to stay afloat.

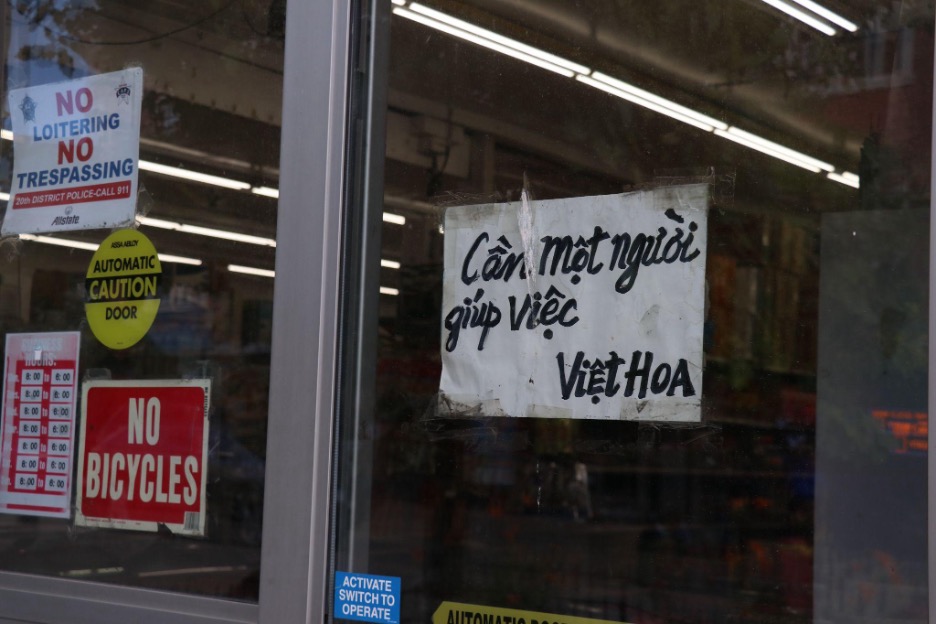

Viet Hoa, one of the first Asian grocery stores in the Uptown neighborhood, saw rising costs in the past months, said Vicki Chou, wife of the store’s owner.

“Because of the trade war, the price is up,” Chou said. The shop sources directly from different Asian countries like China, Vietnam and Thailand.

Tariffs generally translate to a higher price tag for U.S.-based consumers because they affect importation and logistic fees rather than local production costs, according to Lopez. But the economist said large supermarket chains can afford to buy and store additional inventory.

“The bigger stores have more flexibility than the mom-and-pop shops, which will have to face the increase of the price tag,” she said.

Larger corporate retailers may also use their “bargaining power” with the supply chain to “share the pain of tariffs with their suppliers,” Coxhead said.

Customers continue to patronize, but …

Despite these recent economic challenges, longtime customers continue to patronize the stores, but more judiciously.

Willy Rubio, who immigrated from the Philippines to Chicago in 1991, said he and his family would regularly look for discount coupons when doing their shopping. They would also monitor social media for half-price deal announcements.

The 62-year-old, who worked as a laborer in the city, said he usually buys vegetables and condiments exclusively from Asian stores.

“And they (prices) are way, way up high this year,” Rubio said. Even staple commodities like eggs have doubled or even tripled the cost, he added.

“We have no choice because everywhere we go, the prices have all increased. You have to find the good deal.”

A manager of a big Asian grocery chain in Chicago who requested not to be named due to legal reasons estimated 90% of the supermarket’s products will be affected by tariffs. As early as the summer, customers have been “buying less,” the manager said at the time, citing the “domino effect” of tariff announcements.

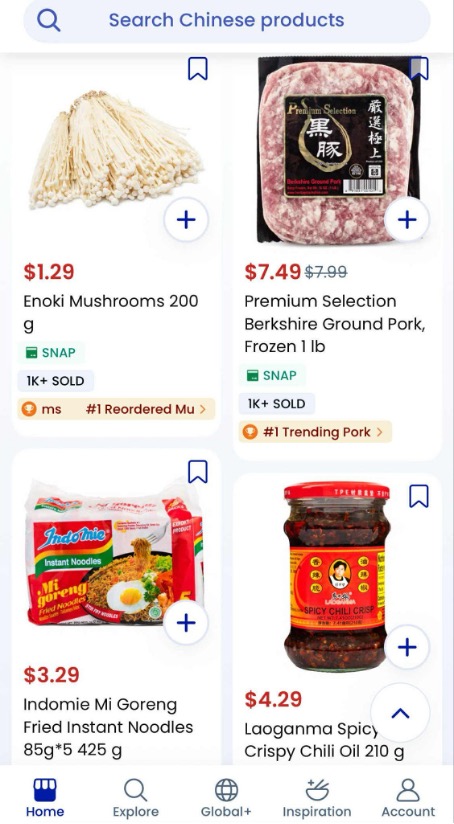

Meanwhile, some shoppers are also considering other factors like convenience, prompting them to shift from in-person grocery shopping to ordering products online from digital Asian supermarkets like Weee!

The California-based company, the largest online Asian grocery store in the U.S., offers products from the eastern, southern and southeastern parts of Asia.

Why cultural grocers deserve their space

Both regular customers and longtime staff of Asian grocery stores stressed the importance of maintaining the international, immigrant-owned businesses, especially in a diverse country like the U.S.

The tariff-fueled price hikes will likely hurt the Chinese community, Zhang said. But she remains confident her countrymen will keep on supporting these businesses.

“When they visit these markets, they have friends there, they have a sense of community,” Zhang said.

“I know the tariff situation is very hard, but I feel like a lot of Asian communities depend on these markets,” she said. “With the price increase, I don’t know how much more people will be able to shop there as often, and be able to connect with their culture and find their favorite foods, and just feel like they fit in.”

Despite all these, Zhang is willing to compromise – if it means getting a quick, simple taste of home.

Alyssa Rola is a recent graduate of the Medill School of Journalism.