By Leah Vann

Medill Reports

Linette Aleman, 20, rubbed her hands together as she sat in Los Gallos restaurant on Nov. 17, 2019, recalling the first panic attack she had 11 months ago.

Aleman vividly remembers the episode. She described the feeling of her shoulders rising up uncontrollably, and what followed was a series of physically uncomfortable sensations her conscious mind couldn’t control.

Sitting in the back seat of her dad’s car, she felt her neck tighten, stomach twist and temperature heighten. She managed to mumble, “I don’t feel good,” over and over again until her dad finally pulled the car over.

“My sister, I think she realized something was wrong, so she was like, ‘Ok, count from 100 to 0 slowly,’” Aleman said. “And I was like 100, 99, 98… once I hit 85, I just started sobbing and screaming, ‘I can’t breathe.’”

Aleman said the attacks continue to hit her and that she can’t predict when they will happen or pinpoint their triggers. It could occur during a car ride out to dinner, on the train or during a meeting at her internship at Year Up Chicago.

It’s been a year since Aleman sought clinical help at Alivio Medical Center, a federally qualified health center in Little Village, where she received a prescription for Xanax to ease the symptoms of her anxiety panic disorder. But her family urged her to stop taking the medication after a month. She no longer takes Xanax for her disorder.

“They were afraid I would get too dependent on them,” Aleman said. “I didn’t have health insurance at the time. When I went to Alivio, they said it was going to be $10, but the bill ended up coming out to be 60 something.”

Many other people in Chicago’s Little Village community live like Aleman, but don’t know where to turn for treatment. Former Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel closed six of the 12 mental health clinics run by the Chicago Department of Public Health in 2012, including one in the Back of the Yards, another Latinx community

The Lawndale Mental Health Clinic in Little Village is one of five public clinics that still operates — one of the remaining clinics was privatized in recent years. But, many surrounding mental health clinics, like Saint Anthony Hospital, share the burden of extensive waitlists.

In response to the city’s closing of publicly-funded clinics, Arturo Carrillo, a program manager for a community wellness program at Saint Anthony Hospital, spearheaded a 2018 study to examine the state of mental health in Chicago’s Latinx community.

The study surveyed nearly 3,000 Latinx adults currently living in Chicago’s southwest side, including Little Village, and found that almost half of the respondents reported having depression while 39% reported problems with anxiety.

According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, the Latinx community labels mental illness as being “crazy,” and 33% of Latino adults receive treatment each year, compared to the U.S. average of 43%.

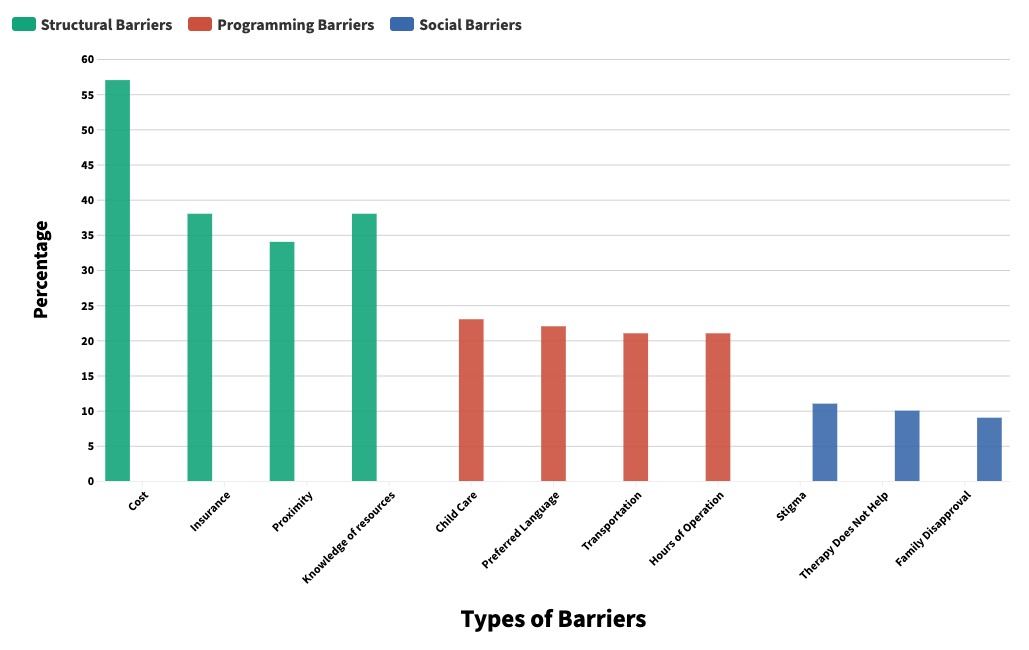

Despite the stigma, Carrillo’s study found that Chicago found that 80% of its Latinx community wants professional help. The top barriers were cost, lack of insurance, proximity and not knowing where to seek help.

“Little Village is not an area that gives people many options,” Carrillo said. “When we think about the public sector and city clinics, they haven’t been promoted because there’s been an offer to close publicly funded clinics. When you give people the option, people are overwhelmingly wanting to go.”

Dr. Margarita Alegria, the Chief of Disparities Research Unit at Massachusetts General Hospital, has been the principal investigator of studies on minority mental health through the National Institute of Health. She says that these numbers mirror a wider sentiment on the national level.

“Even in the elderly, which is a population that is very skeptical, we’re getting around 72-75% of people being willing to accept and come to treatment,” Alegria said. “Lack of insurance is a serious barrier. We still find a lot of people who do not even have a primary care provider that can give them a referral or connect them to services.”

In the City of Chicago’s 2020 Budget Plan, Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot allocated $9.3 million to the Framework for Mental Health, which strengthens trauma centers in the six remaining city clinics.

“We are left with more questions than answers,” Carrillo said. “We did see that the mayor would fill out six vacant positions, but the details were vague. They stated that there are 170,000 people who need services and we don’t see the proposal meeting the needs of the city.”

Some of the funding Lightfoot proposed helps federally qualified health centers, which provide integrative care to families at lower costs. This includes Esperanza Community Health Centers, which has four locations in Chicago’s southwest side, including one in Little Village.

But Carrillo doesn’t believe funding FQHCs will help serve the greatest volume of patients, since they already receive funding from the federal government.

“If the public sector can increase its funding, there can be sustained health investment like what we see in the public school system as a public service offered to residents of the city,” Carrillo said.

Esperanza’s Little Village location has two bilingual psychiatrists. Its integrative care is something Justin Hayford, director of government and foundation relations at Esperanza, says helps combat the stigma surrounding mental health that exists in the Latinx community.

For example, Hayford said the clinic may see a patient who comes in to see a primary care provider about asthma, but also opens up about self-harming behaviors. In these cases, the provider can walk the patient down the hall to a psychiatrist. Esperanza also leads programs that extend outside the clinic, like immigration physicals and on-site counselors in schools.

“It isn’t just a doctor in a box,” Hayford said. “We address the concerns the community brings to us.”

Alegria notes that even though people are willing to seek help, the approach sometimes has to be different than traditional psychiatry or therapy.

“There’s a lack of linguistic competency, not just in language, but also feeling that this person will know what they are talking about,” Alegria said. “The problem has been very medically driven approach versus more of a psychosocial approach.”

In Chicago, nonprofits like Erie Neighborhood House and Enlace are taking the psychosocial approach to mental health outside of the traditional clinical setting.

Comfort in groups

Erika Flores, 38, leads a free women’s empowerment group on Tuesday mornings at Erie Neighborhood House, a nonprofit human services agency in Little Village for Chicago’s immigrant communities.

As a community support specialist, Flores is not a licensed counselor, but believes the women’s empowerment group is a safe space for women to talk to others like them.

She begins the discussion asking the women about their weekend. While she plans to discuss coping strategies for depression and anxiety, the first hour morphs into an open discussion of domestic conflicts with spouses.

“I feel like they have that comfort, they get to know these people and know their stories,” Flores said. “They know, ‘I’m not the only one going through the situation that I’m going through.’”

Estela Silva, 42, said that while she went to a psychiatrist for her anxiety at Esperanza, she wasn’t prescribed medication. Instead, she attended a few talk therapy sessions for her anxiety.

Silva said that Flores provides a more comforting environment because she relates and shares her own experiences on tough topics.

Enlace, a community nonprofit based in Little Village assisting in health, immigration, education and violence prevention, also hosts these groups at the local schools.

Sahida Martinez, 47, a community health worker at Enlace, leads the women’s empowerment groups. She believes they’re important for immigrant women who feel intimidated to open up to someone who doesn’t understand what it’s like to be Mexican.

“Each woman has a different history of their life,” Martinez said. “We don’t like to go to the doctor to talk about emotions. We don’t believe in depression or anxiety. In this group, each woman has the opportunity to express their pain.”

But as a researcher at Massachusetts General Hospital, Alegria said the psychosocial approach isn’t enough for those who suffer from more serious mental illnesses. As a result, the Massachusetts General Hospital’s clinic extended its hours to the evenings on weekdays and added weekend sessions. The hospital also provides transportation funding for patients or offers phone sessions.

Carrillo hopes that Chicago’s new funding can expand medical resources in places that need it.

“It’s easy for the city to fund places already funded on the federal level,” Carrillo said. “At the end of the day the city is relying on what can be funded, that’s putting a Band-Aid on a bigger problem.”

Silva’s interview was conducted through a translator.

Correction: There are five Chicago Department of Public Health clinics that still operate. One of the remaining clinics was privatized in recent years.