By Layna Hong

Medill Reports

Mai Le, 29, had been in the U.S. for less than a year when Donald Trump was elected for his first presidential term.

“I had already liked him, but I didn’t fully understand his policies at that point,” Le said in Vietnamese. “I just liked the way he spoke and how decisive and tough he is.”

Le is originally from Vietnam and now works at a nail salon in the suburbs. She said during Trump’s first term, she felt like “everything was better.” In 2020, Le was unable to vote but said she still wanted to show her support for Trump in another way. So she traveled to Washington, D.C., on Jan. 6, 2021, for a rally turned insurrection. Le was later arrested and sentenced to prison time for her role in the insurrection.

“It was crowded like a BLACKPINK concert,” Le said. “You feel the atmosphere, and you want to do your part to support.”

Le, who now lives in the Chicago suburbs, isn’t unique among Vietnamese Americans, who have long leaned politically conservative.

Out of the seven Asian people arrested for the Capitol insurrection, five of them were Vietnamese, including Le, according to an analysis from Seton Hall University School of Law.

Even Trump has noticed the Vietnamese community’s affinity for right-wing politics. Last year, he visited Eden Center, a predominantly Vietnamese shopping center outside of Washington, D.C., as part of his presidential campaign.

“The Vietnamese community loves me, I love them,” Trump said.

Van Huynh, the executive director of the Vietnamese Association of Illinois, said in the 1980s and 1990s, when many Vietnamese refugees resettled in the U.S., the Republican Party was in power, so there’s an underlying sense of loyalty.

“What people talk about is the Republican Party was the party that allowed them to come to the United States,” Huynh said. “I think now, the Republican Party is very different.”

And Vietnamese American politics are changing, too, according to 2024 AAPI Data. More Vietnamese Americans identified and leaned toward the Democratic Party, as opposed to the Republican Party.

In Chicago, Vietnamese American organizers are trying to unify their community to mobilize on government policies that harm them, like cut public funding and harsh immigration policies.

Reliance on social services despite leaning Republican

The largest waves of Vietnamese people arriving in the U.S. came with the Refugee Act of 1980. Other pieces of legislation passed during that time provided more financial assistance and relocation aid to refugees starting their lives over.

“They’re a people who came out of a war being very grateful for a second country that accepted them,” Huynh said.

Even after these refugee assistance programs were dissolved, many Vietnamese Americans, especially elders, continue to benefit from government programs like Medicaid and food stamps. Now, those programs are under attack from the current Republican administration.

“People, especially low-income folks, have seen over the years programs get created and then programs get taken away,” Huynh said. “And the challenge, then, is to get them to speak out against it.”

VAI tries to help fill the gaps. Its largest program is elderly in-home care.

“I think the Vietnamese community is representative of a larger trend in the United States,” Huynh said. “There is an aging population who is very concerned about the programs and services afforded to them.”

Huynh said a lot of the work VAI does is helping people connect their lived experiences with current policy issues like immigration and health care. It’s a challenge — one Huynh, 36, is intimately aware of.

She said her mother supports cuts to public benefits because she believes people take advantage of the system – even though she herself relied on food stamps when Huynh was growing up.

“I asked her, is that what you were doing, though? Because we were on food stamps,” Huynh said. “And she’s like, ‘Well, that was different. I needed it.’”

Community is tighter than politics

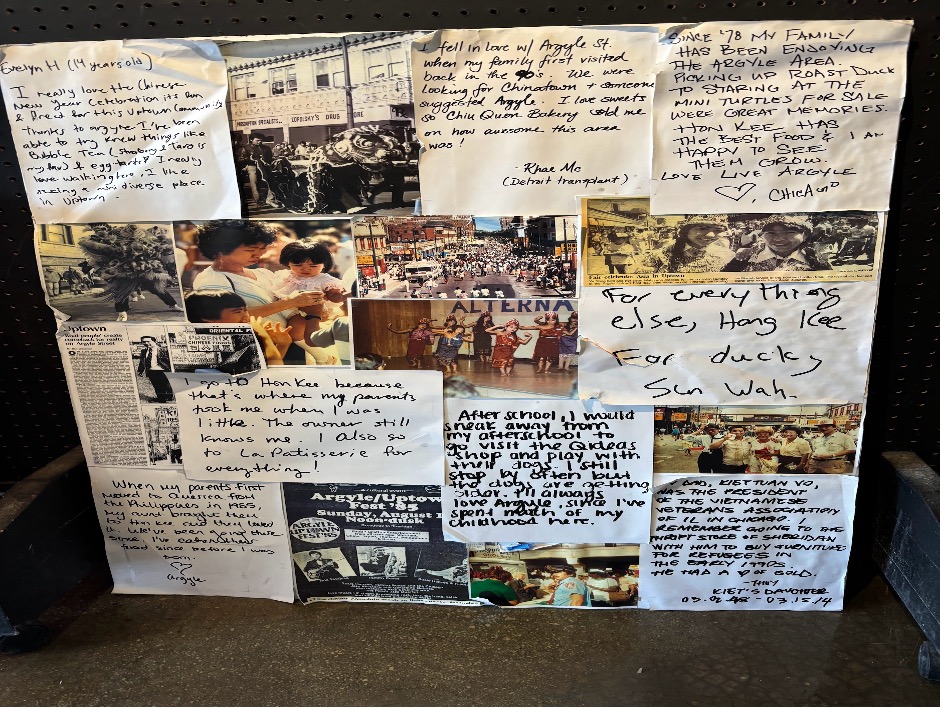

According to APIA Vote, Vietnamese people make up the sixth largest Asian ethnic group in Illinois, with many of them in the Chicagoland area. Many Vietnamese refugees resettled in the city’s Uptown neighborhood after the war, where they formed Asia on Argyle, a walking street lined with mainly Vietnamese restaurants, shops and organizations. It’s sometimes referred to as Chicago’s second Chinatown.

While the North Side corridor maintains its reputation as Chicago’s hotspot for Southeast Asian communities, the population of Vietnamese Chicagoans is not as concentrated now as in the 1990s.

Hac Tran’s parents left Vietnam the day the war ended and resettled in Chicago, where they were heavily involved with VAI in Tran’s childhood.

“From my experience growing up in the Vietnamese community, especially being part of the VAI, every Lunar New Year, every kind of holiday that we had, it was always a pretty strong-knit community,” said Tran, 39. “But I feel like that’s kind of changed over time. A lot of people have moved away from Chicago and moved away from this area.”

Tran works closely with Argyle’s shops and businesses through HAIBAYÔ, an initiative dedicated to preserving the street’s cultural history as a hub for Vietnamese Chicagoans.

Despite political polarization, people like Tran still want to maintain and build community.

Tran said he knows many Vietnamese people who voted for Trump.

“I know who’s Republican on this block” of Argyle Street, he said. “I know who’s a Trump supporter, but I’m not trying to actively engage in like, ‘Why did you vote for this guy?’”

He said he doesn’t see Vietnamese Trump supporters as enemies.

“It’s our duty as the second generation to have those hard conversations with elders and talk to them and explain to them what they may not know,” Tran said.

It’s a near universal experience for Vietnamese Americans to have family members who lean right wing, whether it’s direct or extended family.

“My family is pretty left, and they’ve always voted Democrat,” Tran said. “Of course, there’s certain people in my family that vote right, but they’re kind of the outliers.”

Randy Kim grew up in the Chicago suburbs and identifies as a Queer Viet-Khmer American. He said he tries not to engage with conservative community members, even though he’s aware of their existence.

“I’m more of an observer. I don’t believe I feel like I have to compromise my values to fit certain things in,” Kim said. “But I could still hold graciousness and grace.”

How history influences politics

Overall, it’s complicated.

Tran points to history, Vietnamese politics and even an error in translation as possible reasons for why some diaspora skew Republican. The same word, “cộng hòa,” is used in both the official names for the former Republic of South Vietnam and the GOP.

Many Vietnamese refugees displaced after the war have deep anti-communist sentiments and therefore see the Democratic Party’s policies and platform as similar to the government they fled.

Tran emphasized the importance of “trying to understand why people vote that way and understanding their lived experience.”

“When you have those conversations to try to explain to them that the (American) left is not, in fact, the Vietnamese Communist Party,” he said.

There are also differences between waves of immigration. Fifty years after the end of the Vietnam War, Vietnamese people are more likely to immigrate through family members or for work, as opposed to seeking asylum, according to 2023 research from the University of California at Berkeley.

But even without the shadow of war, more recent Vietnamese immigrants, like Le, can also share similar sentiments to the older generations.

“Vietnam is beautiful, but it’s a communist country so there’s no freedom,” she said. “I wanted a better future.”

And even though Vietnamese Americans first came to the U.S. as asylum seekers and refugees, the majority of the diaspora today has legal documentation or American citizenship.

For Le, this is why she believes in Trump’s immigration policies.

“I’m an immigrant, my parents are immigrants, so I can’t hate immigrants,” she said. “But you have to come here legally.”

Federal agents arrived in Chicago at the beginning of September as part of Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s “Operation Midway Blitz,” with the goal to arrest immigrants and crack down on sanctuary cities. Agents have been arresting and intimidating people all over the city and the suburbs, including in North Side neighborhoods home to immigrant communities.

In October, Illinois state Rep. Hoan Huynh (no relation to Van Huynh) alleged that federal agents pointed a gun at him and his staffer when he was driving through the Irving Park and Albany Park neighborhoods to warn community members about ICE.

Southeast Asian refugee communities across the country have been targeted for deportation, like in California, Minnesota and Rhode Island.

VAI’s Van Huynh said part of her organization’s job is to keep community members safe through networks of care.

“We’re creating networks for people to be able to call on each other, check in with each other,” Huynh said. “We’re building that at a community level, especially around these political issues.”

Working toward common causes

Walking down West Argyle Street, alongside job postings and event flyers in different languages, many businesses also show their support for state Rep. Huynh in their windows. Huynh, a progressive Democrat, has represented Chicago’s North Side since 2023 and is Illinois’ first Vietnamese elected official.

In 2024, he won an overwhelming re-election against the Republican candidate, Terry Le (no relation to Mai Le), who is also Vietnamese.

“It’s obviously easier as an incumbent to gain votes, but even in his first election, he did have a really large margin,” said Huy Nguyen, the chief of staff for Huynh’s office.

In 2022, Huynh won with 90.5% of the vote. The following year, he won by 87.7%.

Nguyen said Huynh appeals to Vietnamese Chicagoans on issues they care about, such as affordable housing and access to health care.

“Even if they don’t understand that the Republican Party might be trying to strip those things away,” Nguyen said, “they understand Hoan is fighting for these things down in Springfield.”

Like all communities, there’s nuance. Van Huynh said she has noticed more elders voting Republican in recent years when VAI has taken people to the polls.

“A lot of Vietnamese people get their information from YouTube, and these informal news networks that tend to incite some of our deepest fears,” Van Huynh said.

Sometimes, Van Huynh said younger Vietnamese Americans who grew up in the U.S. can have a better understanding of systemic issues like gentrification and funding cuts and how that plays into their elders’ lived experiences.

However, the younger generations can lack the tools to start conversations about it with their community.

“A lot of young people are not fluent in Vietnamese, and that makes it really difficult for them to connect with seniors in the community,” Van Huynh said, “but also with their families, right, to be able to talk to them about the issues that they care about.”

Besides speaking to one another, publicly protesting political and social issues can also be difficult, according to Sarah Nguyễn (no relation to Huy Nguyen), a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Washington who has researched how Vietnamese diaspora communities get and share information.

“There were a lot of people in the U.S. very much against Vietnamese people coming to the U.S.,” Sarah Nguyễn said. “So, one way to be able to survive, get food on the table, get a shelter over your head, not be attacked on the street, is to keep your head down, keep quiet, don’t talk about politics.”

But as the country’s fourth-largest Asian ethnic group that’s only growing, Vietnamese American voices are becoming more politically influential.

In August, despite the near 90-degree heat, VAI organized community members to rally around the closing of Uptown’s Weiss Memorial Hospital after the facility failed to meet federal standards and lost its Medicaid and Medicare funding. One sign in Vietnamese read “Invest in our community, keep Weiss Hospital here.”

The hospital served as a vital health care facility for many low-income Vietnamese Chicagoans.

“Growing up, my family and I relied on Medicare and Medicaid, my parents are on Medicare, and so this hospital is very personal to me,” Rep. Huynh said to the crowd. “I’ve been a patient at this hospital numerous times. My family’s been patients at this hospital numerous times.”

Some community leaders hope issues like the hospital closing will help Vietnamese Americans better understand the value of programs like Medicare and Medicaid, and elected officials’ stances on those issues. To connect the dots, people need access to quality information.

Sarah Nguyễn became interested in studying more about how Vietnamese diaspora communities get their news information and talk about politics after observing her parents’ habit of having YouTube videos constantly in the background.

In Nguyễn’s research, she conducted many workshops around the country with different Vietnamese diaspora communities around intergenerational conversations about how to find, share and trust news information.

“These workshops were really about just getting people to talk about this, which is really difficult because we don’t like to talk about politics,” Nguyễn said. “So how do we make it nonpolitical when it is inherently political?”

One of the focus groups was in New Orleans, where the Vietnamese community was displaced twice: first after the Vietnam War and then again in 2005 due to Hurricane Katrina. Nguyễn said for many of the participants, it was their first time being asked how they felt about politics.

“Historically, the majority of the institutions that come in to ‘help’ them are only about understanding them as refugees or victims,” she said.

During the 2020 presidential election, Nguyễn sat down with her mom and convinced her to vote for the first time since arriving in the U.S. 30 years ago. She took the time to explain the policies of each candidate on the ballot.

“I have my own politics, but I’m more interested in being able to see how this community of people, this diaspora, can be able to feel comfortable at talking about (politics), to be able to process it together,” Nguyễn said. “So that we can make sense of what is actually more beneficial for us as a whole.”

Layna Hong is a recent graduate of the Medill School of Journalism.