By Christiana Freitag

Medill Reports

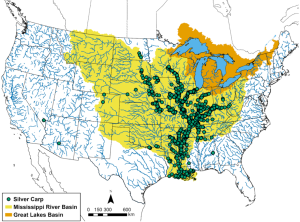

When loud barges pass along the Mississippi River, a flurry of oversized silver carp can be seen leaping into the air. These noise-sensitive invasive fish escaped from aquaponic ponds on the lower Mississippi in the 1990s, and continue to pose an ongoing ecological threat to the Great Lakes.

As filter feeders, invasive carp can quickly overtake and overpopulate ecosystems, impacting the food sources of other native fish, according to aquatic nuisance experts in Illinois.

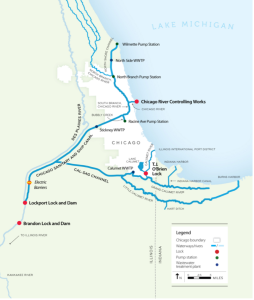

Since then, Mississippi River border states, including Illinois, have been prioritizing efforts to mitigate invasive carp from continuing their journey from the Upper Mississippi to the Great Lakes. In February, however, federal freezes of funding to the Illinois Department of Natural Resources (INDR) have delayed the rollout of Illinois’ Brandon Road Lock and Dam, a $1.15 billion project to block Asian carp at the mouth of the Illinois River before they can reach the Great Lakes.

Electric fences in the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal at Romeoville have prevented the fish from reaching the Great Lakes via the Illinois River. But in recent years, carp environmental DNA (eDNA) from scales and feces have been found in waters even closer to Lake Michigan.

Although the more secure lock infrastructure project has been stalled since February, this delay hasn’t impacted the IDNR’s aquatic nuisance programs in finding innovative means to halt movement of the various carp species from the Mississippi River to the Great Lakes.

“If they’re ever in the Great Lakes Basin, it’ll be impossible to get rid of them,” said Cory Suski, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign professor in the Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Sciences.

So how did these fish get here from Asia in the first place? In the 1970s, invasive carp species were imported as algae-cleaners for farm pond aquaculture. Dr. Austin Happel, a research biologist at the Shedd Aquarium, theorized either due to flooding or hurricanes, Asian carp escaped farm ponds and entered the Mississippi River Basin.

“The genie is probably not likely to go back into the bottle,” said Brian Schoenung, program manager of the IDNR’s aquatic nuisance programs. “But we can utilize a variety of tools to manage populations at an acceptable level.”

Many of these tools involve adding “non-physical barriers” to waterways to deter carp from moving upstream. The IDNR and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers have experimented with carbon dioxide and even sound barriers, in addition to electric fencing, to stop carp in their tracks. But none of these efforts are foolproof, Shoenung said.

Given the sheer volume and density of carp populations, the IDNR has also embraced another solution: market the fish.

Shoenung’s team have turned to the commercial fishing industry to fish carp for a variety of uses, including pet food, fish oils, fertilizer and human consumption. Through a commercial fishing incentive program, the IDNR has given fishers a competitive 10 cents per pound for fishing carp.

“The only limiting factor is having commercial fishers to actually go out and fish,” Schoenung said. “We’ve lost a lot of that industry. We’ve shifted away from domestic fish harvest and consumption to basically importing everything.”

Despite downward trends in domestic fishing, the IDNR’s incentivized carp harvest program has removed nearly 27 million pounds of invasive silver carp in the Illinois River since the program began in 2019.

Similar efforts are now being implemented throughout the Ohio and Mississippi rivers, Schoenung said.

“Folks are happier because they can go out and boat without fear of getting T-boned in the side of the head by a jumping carp,” Shoenung said.

But for dealing with an invasive fish that grows quickly and spreads rapidly, there isn’t a catch-all solution to keeping carp contained. Aquatic researchers such as Suski and Happel are interested in another theory of what may be stopping carp from entering the Great Lakes: Chicago’s polluted rivers.

“The conclusion is that there’s something in the water coming from the Des Plaines River and the Chicago area waterways,” Happel said. “Something that’s causing these carp to not move up farther, and that’s likely something to do with wastewater and effluent and pollution and contaminants.”

Chicago’s wastewater flows away from the lake via the Chicago River, due to a century-old engineering wonder that reversed the course of the river to prevent the spread of disease through the city’s lake water supply.

To understand this phenomenon, Suski has been studying the gene expression of carp when they enter polluted water like the Chicago River. He’s found that due to a mysterious pollutant, carp become “stressed” and stop moving altogether.

“It’s a really cool mystery to try and solve,” Suski said. “Like, what is going on with these crazy fish?”

But this theory comes up against a decades-long effort to clean Chicago’s waterways.

“There’s a number of things that are all happening to make the water (in the Chicago River) cleaner, which is a great thing, right?” Suski said. “But if there’s something inadvertently in the water that’s making the fish suddenly stop moving, we’d like to know what that is.”

Suski hopes future funding can allow him to solve this carp conundrum. But carp mitigation is a massive and imminent issue that can’t rely on one theory alone, Schoenung said.

Beyond deterrence efforts and incentivized fishing programs in Illinois, there’s a push for a coordinated, statewide effort across the Mississippi River Basin to tackle this invasive species concern.

“It would put the Mississippi River Basin at the same level as, say, the Great Lakes, and bring that attention and focus to the issues facing interjurisdictional fish, particularly threats like habitat loss and invasive species, which is huge,” Schoenung said.

Schoenung is a member of the Invasive Carp Advisory Committee under the Mississippi River Interstate Cooperative Resource Association, or MICRA, which has been advocating for legislation to mitigate invasive aquatic species across all 31 states that fall within the Mississippi River Basin.

On Feb. 24, MICRA presented House Bill 15.14 in Congress to establish the Mississippi River Basin Fishery Commission, a proposed interstate governing body to manage the ecological concerns of the fourth largest watershed in the world.

The bill has yet to be voted on, but if passed, Shoenung said this legislation would codify much-needed governance across the entire Mississippi River Basin to mitigate the ongoing threat of invasive carp.

Despite stalls to the Brandon Road project and an anticipated inter-agency commission, there’s a clear consensus among Illinois environmentalists for a continued push to prevent carp’s invasion front from moving any closer to the Great Lakes.

“Anytime we’re not stopping carp,” Suski said, “there’s a chance they’re going to get through.”

Christiana Freitag is a graduate journalism student at Medill, specializing in health, environment and science reporting, with a concentration in data journalism. You can follow her on LinkedIn and contact at her at: christianafreitag2025@u.northwestern.edu.